Dear Mother: the story of 2nd Lieutenant Dudley Cautley Stewart-Smith

At the outbreak of the First World War, Britain’s Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener launched a recruitment campaign for men to volunteer to be trained as regular soldiers. Additionally, there was a need for men to serve as officers and command the ordinary ranks. Any man over 18 and with a private school education was considered potential officer material. Many of these young men rushed to enlist, often thinking like others, that the war would be short-lived and they wanted to do their duty and not miss out. Dudley Cautley Stewart-Smith was one of these young men. The casualty rate among the junior officers was very high during the war, but Dudley was very fortunate; he survived the First World War and indeed went on to serve in the Second. This is his story.

Early life

Dudley Cautley Stewart-Smith was born in London on 12 October 1894, the eldest child of Dudley Stewart-Smith and his wife Katherine (née Cautley). In 1901, the family was living in a wealthy area of Paddington and Dudley Senior was a barrister and solicitor-at-law. The family employed 5 servants and at that time had 3 children, Dudley C and his sisters, Ellen and Millicent. Their youngest children were born later, Katherine in 1905 and Ean in 1907.

Dudley (2nd row down far right, standing) at Winchester College in 1910 (Photo courtesy of James Stewart-Smith)

Dudley attended prep school at Sandroyd in Cobham, Surrey and then went on to Winchester College in Hampshire in 1907. He is listed in the 1911 census as a 16 year old boarding student at Winchester. After leaving Winchester, he spent six months with a French family in Dieppe before he went to University College, Oxford. By the time that war broke out in 1914, Dudley had just completed his law studies.

Outbreak of war

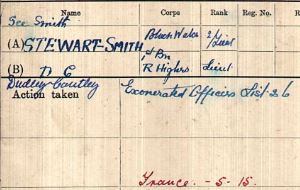

Dudley immediately volunteered to join the army and an entry in The London Gazette (1 December 1914, p.10932), shows that he was initially assigned to the 2nd Public Schools Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) as a temporary 2nd Lieutenant on 31 October 1914. Dudley was just 20 years old. His commission was subsequently confirmed as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Highlanders (Black Watch); this was a reserve battalion. This is recorded in the Supplement to The London Gazette, 7 July 1915, p. 664. From his Medal Index Card it is clear that he was soon transferred to a regular battalion with the Black Watch and he arrived at the Western Front in May 1915.

Dudley’s war

Dudley’s war with the Black Watch was very well documented as he wrote many letters home and later kept a personal diary recording his experiences. He wrote to his mother very regularly and described his days in some detail. His original pencil written letters were kept by his family and have been transcribed, providing an insight into the life of a young officer at war. He kept his family informed of his locations and often described the actions in some detail. Shortly after he landed in France with the 2nd Battalion Black Watch in May 1915, he very soon wrote to his mother:

May 18, 1915

Dearest Mother

I sent you a card this morning. We all drove down to the docks and got our kits and then drove to Honfleur five miles outside Havre where most of the camps are situated.

2nd Black Watch, Bareilly Brigade

Meerut Division, Indian Exped Force A

The Bareilly Brigade had been formed in 1914 as part of the Meerut division of the British Indian Army, and Dudley’s battalion, the 2nd Black Watch, had become part of that new brigade. In May 1915 the Black Watch battalions were actively involved in the Battle of Festubert and Dudley wrote home at that time:

Sunday May 23rd 1915

Dear Mother

Here I am in the thick of it. I am writing this dug out in the trenches, the Germans being about half a mile away. I am in the reserve trenches.

From May until September, he sounded very upbeat and was keen to reassure his mother that he was ‘alive and well’, and indeed enjoying himself: ‘I am quite well and getting on famously so far’. He often requested items to be sent to him: ‘Will you send my breeches and dark brown boots also a stick of shaving soap and a piece of Wright’s Coal Tar soap’. In general he was satisfied with his billets and the food: ‘Food and drink we have in plenty’.

His letter to his Mother of the 1 August described his first close encounter with the enemy: ‘Last night I came into action for the first time and my efforts were successful’. He went on to describe the action. He wrote a particularly interesting letter to his father on 15 August, in which he asked: ‘What is the opinion at home about the duration of the war? On the face of it out here, it might go on for ever’. Also, he commented that: ‘The general feeling here is: – here we are, here we’ve got to stay; to attack is absurd as it means the loss of thousands of lives, so strongly are both sides entrenched and wired, also the winter is coming. What is the opinion of those in the know at home? We should so like to know.

However, his situation changed in September, as an attack did indeed occur. In late September 1915 the Black Watch Regiment took part in the Battle of Loos, which proved to be very costly as they lost hundreds of men in that battle.

Sept 23rd

Dear Mother

We moved up nearer the firing line last night. I shall be unable to write to you for a day or two as I shall be otherwise engaged in the business for which I came out. I am alive and very well.

DSS

On 26 September he sent a field service post card. He amended the pre-printed messages to read as follows:

I am well.

I have been admitted to hospital.

I am sick and slightly wounded – gassed.

Then he added:

On NO account try and come across

Dear Mother

I am alive after rather a terrible experience. I got gassed by our own gas but did not feel effects until 5 or 6 hours later.

He was sent by ambulance train to the Duchess of Westminster’s (No.1 Red Cross) Hospital at Le Touquet. On 27 September he wrote: ‘The battalion was cut to pieces. Only 5 officers and 200 men were left. ….. I was very lucky indeed to escape with my life but I am very poorly and have lost all my kit’. After a short stay in Le Havre, Dudley may have had some home leave as there was a gap in his letter writing to his mother. His eyes were permanently damaged due to the gas and in later life he had to use a monocle.

Mesopotamia

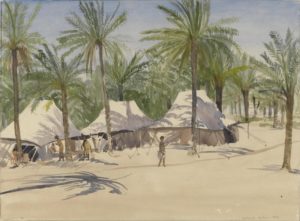

By November 1915, Dudley had recovered enough to re-join the 2nd Battalion in France and to be sent with them to Mesopotamia. The 2nd Battalion had been withdrawn from France for operations against the Ottomans in Mesopotamia to assist with the attempted relief of the siege at Kut-el-Amara.

On 5 December they embarked from Marseilles and the journey can be tracked from Dudley’s letters home; stopping off in Alexandria, Port Said, via the Red Sea to Aden, into the Persian Gulf, spending Christmas Day 1915 aboard HMT Royal George. They transferred to HMT Nizam and then onto river barges for the journey to Basra.

On reaching the front line in Mesopotamia, Dudley wrote to his parents, but kept the letters as a diary as he could not get them sent home. On 10 January 1916 he told his father that, ‘War out here is a thousand times worse than in France’, and that he had been made transport officer, following an ‘awful action’ that his battalion had just endured. He was almost certainly referring to the Battle of Sheikh Sa’ad. The losses at Battle of Sheikh Sa’ad were so heavy that the Battalion had to be merged temporarily with another Highland battalion which had suffered similarly and again more casualties were suffered at the Battle of Wadi on 13 January. On 16 January 1916 he told his mother that food was ‘very scarce and that they live on porridge, biscuits, bully beef, bread and drink the water from the river which is filthy dirty’.

The Battle of Hanna on 21 January 1916 was a particularly brutal action for the 2nd Back Watch and the losses were great. Dudley wrote this next letter home after the Battle of Hanna, finding himself briefly in command of his decimated battalion aged 21 years. It was the darkest letter he wrote to his mother.

Jan 23rd 1916

Dear Mother,

Up to the present, I am alive and well.

On the 21st the Regiment was in an awful action being reduced now to two officers and 185 men. I am left in command of the battalion and hold a position to which I am quite unsuited.

We have had torrential rain and, of course, there is deep mud. We are trying to get tents pitched and some sort of camp formed. I have not had my clothes off for over a week. I have been drenched through and through and have hardly any change of clothing.

When I rode into camp yesterday I had to be lifted bodily off my horse and then I did a faint. I was so stiff with cold and pain and of having been nearly 24 hours in and out of the saddle continuously.

The sun is out today and I am drier and warmer. I also got a night’s sleep.

In the event of my death, remember that I have a box of property at Oxford. Will you send the enclosed cheque to Mrs Johns.

On the 21st we had two officers killed and five wounded. There is just myself and another youngster with a few months’ service. Also the Quartermaster. You read of the horrors of war but you have to come here to see it. I often wish for a bullet to end it.

Love to you all,

Yours aye,

DSS

Dudley was mentioned by name in ‘With a Highland Regiment in Mesopotamia 1916-1917’, by Capt H J Blampied (Bombay: The Times Press, 1918, p.22), which confirmed that: ‘The following day what remained of the Battalion was moved across the river, and 2nd Lieutenant Stewart Smith assumed command, to be followed shortly by Captain Crake’.

By late February 1916 Dudley had been taken ill with typhoid fever and dysentery and was unable to write his own letter home, so he dictated a letter to one of the Army Chaplains.

Rev. J. H. H. McNeill

Chaplain, Church of Scotland

IEFD

28th Feby: 1916

Dear Mrs Stewart-Smith

The enclosed is a letter dictated by your son. He arrived here from the Front yesterday with fever. His temperature is better today and generally we have every hope that his description of his condition is correct and that he will go on well and quickly towards recovery.

Dudley was invalided to India on 29 March 1916, where he spent some time recovering and while there he is known to have visited Deolali transit camp.

His battalion remained in Mesopotamia and continued to play their part in the battles leading up to the surrender at Kut on 29 April 1916.

Dudley returned briefly to Mesopotamia. He left Karachi on 13 July 1916 and disembarked in Basra on 16 July. He was advised that the glare of the sun could do permanent damage to his eyes, so he was invalided again to India on 26 August 1916.

After the conclusion of operations in Mesopotamia, the 2nd Black Watch moved to Palestine and took part in Allenby’s successful action at Megiddo and ended their war there in 1918. However, Dudley is known to have been invalided to England on 4 October 1916 and once recovered he was transferred to the 1st Battalion and found himself back on the Western Front in February 1917.

Back in France

Roll Call of the 1st Battalion, Black Watch (Royal Highlander Regiment) outside their billets, Lapugnoy, 10 April 1918 (© IWM Q 10878)

From April to June 1917 the Black Watch battalions were involved in the Arras offensive. July 1917 saw six battalions of the Regiment taking part in the Third Battle of Ypres and the endeavours to extend the Salient.

The spring of 1918 brought in the final massive German offensive. On 8 April Dudley’s battalion moved to Lapugnoy village, about four miles west of Bethune. On 16 April they moved to the line in Givenchy and on 18 April they experienced an enemy bombardment and heavy fighting. Dudley was wounded and captured by the Germans that day and thus he entered a new phase of his war as a prisoner.

Prisoner of War

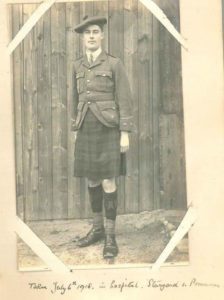

Dudley in his Black Watch uniform in a German Prisoner of War hospital (Photo courtesy of James Stewart-Smith)

It was in April 1918 that Dudley started to keep a diary:

Some account of my stay in Germany as a prisoner of war and of the curious people I met there, beginning on April 18th, the date on which I was captured at Givenchy, when serving with the 1st Black Watch.

The first entry was written on Thursday 18 April 1918:

The Germans attacked Givenchy at about 9 am after a very heavy bombardment. I am not going to attempt a description of the fight, as I saw such a tiny fragment of it. Suffice to say I was wounded in several places and I remember crawling to a shell hole, where a German Red Cross orderly hastily put a bandage round my head, gave me a drink of cold strong coffee & rushed on after his first line of comrades, who had passed about fifty yards beyond me.

In July 1918, Dudley was photographed in his Black Watch uniform in the German Prisoner of War hospital in Stargard in Pomerania.

‘We are almost free’

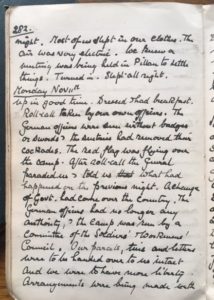

Monday Nov 11th

Up in good time. Dressed and had breakfast. Roll-call taken by our own officers.

The German officers were seen without badges or swords and the sentries had removed their cockades. The red flag was flying over the camp. After roll-call the General paraded us and told us what had happened on the previous night. A change of Govt. had come over the country.

The German officers had no longer any authority, and the camp was run by a committee of the Soldiers’ and Workmen’s’ Council. Our parcels, tins and letters were to be handed over to us intact and we were to have more liberty. Arrangements were being made with Denmark to send us home.

We had been warned to be on the alert the night before owing to a threatened raid on the parcel office.

The General assumed complete responsibility for the order in the camp. The attitude of the Bolsheviks to us was that of friends and not enemies. We need not expect any trouble or violence. We were to carry on just as usual.

In the event of any food shortage the General is going to commandeer all our food and ration us just like a garrison. After telling us this General dismissed. I spent the whole morning sorting and delivering letters. There were arrears of about 6000 letters. I had about 20, all from home except 2 from Mrs Carson. Dinner of potatoes and cabbage.

Read my letters and wrote.

A great day.

We are almost free and no longer under arrogant German officers. It is rather sad to see them stripped of their power and swords. Had a walk in the afternoon. Very cold. Came in and had some tea. Chatted and discussed the general situation.

He finally left the camp on 7 December 1918.

Later life

He married Phyllis Luson in London in 1923 and they moved to India, where in 1924 Dudley served as a Councillor on the Calcutta Municipal Corporation. They had three children. Their eldest daughter Phyllis Jean was born in Calcutta in 1925. The family moved to Ceylon in 1932 as Dudley succeeded T L Villiers as the nominated member of the 1st State Council of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Their other children were born there, Priscilla in 1931 and Geoffrey in 1933.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the family returned to England and in September 1939 Dudley was appointed a Deputy Judge Advocate and took part in his second war in the British Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps. During the War he wrote to his wife nearly every day and he saw service in France, North Africa and Italy.

Dudley as Judge on the bench at the Nuremberg Trial at Fuhlsbüttel Concentration Camp, Hamburg (Photo courtesy of James Stewart-Smith)

Dudley was a natural linguist. He often referred to speaking French in his letters to his mother. During his time in 1918 in the Prisoner of War camp he learnt Russian and German which he was able to put to good use after the end of the Second World War. Between 1946 and 1947 he served as a member of the War Crimes Tribunals.

He held the position of a Deputy Judge Advocate until he retired in 1955. He died in 1957 in Weybridge, Surrey.

James Stewart-Smith wearing his grandfather’s kilt during the Frontline Walk for the Army Benevolent Fund in 2017 (Photo courtesy of James Stewart-Smith)

We would like to thank James Stewart-Smith for sharing his grandfather’s story with us and for providing the letter transcripts and images. James is a Director at Classic Battlefield Tours and on the company’s Facebook site it is possible to find more transcripts of Dudley’s letters. In 2017 James Stewart-Smith wore his grandfather’s kilt whilst completing the Frontline Walk for the Army Benevolent Fund.