Salonika Medic: the story of Captain Arthur Atkins Greenwood

Although it did not appeal to all returning soldiers, some men who served in the First World War formed or joined veterans’ associations. Having been through such a significant experience together, they found they benefited from meeting up with others to socialise, talk about their experience and remember together. The British Legion became the most well-known and dominant association, with a membership of approximately 400,000 by 1938. Other smaller associations were also formed. Sometimes these focused on a specific issue, such as the Limbless Ex-Servicemen’s Association, but there was one formed in the 1920s, which was to recognise those who had served in a specific campaign, and that was the Salonika Reunion Association (SRA). One man who contributed to the success of the SRA was Arthur Atkins Greenwood and this is his story.

Early life

Athur Atkins Greenwood was born in Islington, London, on 29 July 1886, the son of Dr Arthur and Ann Ellen (née Stevens) Greenwood. Arthur had three sisters, Ellen Nina, Ethel Annie and Mabel. He was educated at Christ Church Cathedral Choir School in Oxford and Highgate School in London. Like his father he pursued a career in medicine. In June 1903 he was apprenticed for four years to Master Peyton Todd Bowman Beale, a surgeon at King’s College and an examiner with the Society of Apothecaries. On 6 August 1907, it was certified that Arthur had served his apprenticeship satisfactorily and accordingly he became a Freeman (Yeoman) of the Society and of the City of London.

Arthur qualified as a doctor in January 1909. He undertook various roles at Guy’s Hospital and then became a Medical Officer in charge of the X-Ray department at Hampstead General Hospital. He entered private practice in North London with his father and Dr Charles Harris Langford. On 8 February 1913, Arthur married Phyllis Cobely at Christ Church in Hornsey, Middlesex. His father retired in July 1913.

Arthur’s war

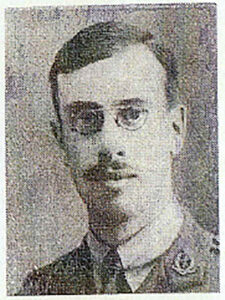

Captain Arthur Atkins Greenwood in 1916, The Mosquito, No. 137, March 1962 p.14 (© Salonika Campaign Society)

Arthur volunteered for service soon after the outbreak of the First World War. According to his Medal Index Card, he was at first a volunteer Medical Officer with the British Red Cross Society. He was sent to France on 29 November 1914, to relieve temporarily a radiologist who was with the British Red Cross. By 1916 he had transferred to the military’s medical arm, and had enlisted with the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was appointed Temporary Lieutenant in May 1916 (The London Gazette, 2 June 1916, p.5468), later serving as a Captain. He was initially attached as a Medical Officer to the 9th Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, which at that time was a training unit at Bovington Camp, Dorset.

HMHS Grantully Castle (Publication Officially sanctioned by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty)

He was soon mobilised at Aldershot and left Southampton aboard the HMHS Grantully Castle on 15 June 1916, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Herbert John Martin Buist, who had been appointed Officer Commanding the 37th General Hospital. The 37th was one of five British hospitals attached to the Royal Serbian Army on the Macedonian Front, also known as the Salonika Front. HMHS Grantully Castle was a former troopship in the Dardanelles during the Gallipoli campaign in 1915 and had been recommissioned as a hospital ship. At that time, the 37th consisted of 37 officers, including 3 padres and 192 men. The 36th General Hospital had left England 24 hours ahead of them, while the 38th General Hospital followed in HMHS Dover Castle.

Salonika

Arthur kept a diary of his service in Salonika, in which he described both the situation in the hospitals as well as details of some of the military actions that affected them. Some years later, parts of his diary were summarised in ‘The Mosquito No. 144, December 1963 p.99 -103’, which was the journal of the Salonika Reunion Association, produced after the war by, and for, those who had served in the Macedonian campaign.

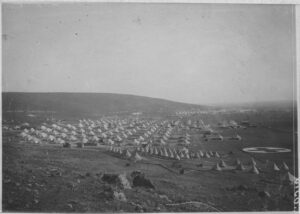

View of 37th General Hospital looking east, with 36th in the distance (Source: Français Opérateur K (code armée)., CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

HMHS Grantully Castle arrived in Salonika (now Thessaloniki) harbour on 26 June 1916, but Arthur wrote that they had to wait for two weeks until 9 July before they disembarked. He and the other members of the 37th General Hospital then travelled by rail to Vertekop (now Skydra). They were left on a plain, close to the railway and 1½ miles from Vertekop station. There the 37th General Hospital was established, alongside the 36th General Hospital, both attached to the Royal Serbian Army, which at that time was no longer able to supply its own medical services, having lost so many medical personnel in the Great Retreat through the Albanian mountains during the winter of 1915 – 1916.

36th General Hospital (Source: Français Opérateur K (code armée)., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

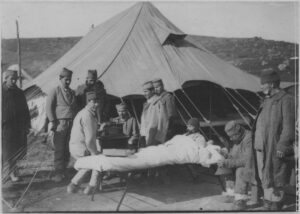

Arthur wrote: ‘For over a week we had no transport and 900 tons of equipment was manhandled to its various destinations to get the hospital going. Officers and men worked alike, with reveille at 4.30 a.m. 108 degrees was registered in one tent. The entrance to the 36th was at the crossing of the rail and Monastir Road. Besides some wards, I was in charge of the X-Ray Department. The Serbian Army was transferred to the front after our arrival, and the first wounded we received came from the bloody fighting on Kaymachalan. On August 4th our 70 Nursing Sisters arrived’.

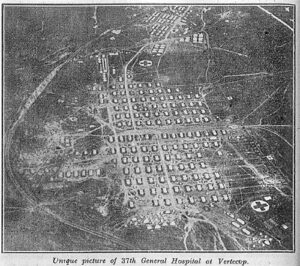

Aerial view of 37th General Hospital, clearly showing the Red Cross sign, The Mosquito, No. 32, Dec 1935, p.106 (© Salonika Campaign Society)

The hospitals were subject to much bombing, which Arthur detailed in his diary. German planes passed overhead daily and on 2 August 1916 five bombs were dropped, one close to the 36th Sisters’ quarters. On 10 August two marquees were hit and on 17 August eight bombs fell. As Arthur noted, the hospitals were clearly marked with red crosses but ‘there was always the excuse of the railway being alongside’.

As was all too common in Salonika, malaria affected the staff as well as the patients, putting an additional strain on the medical services. The shortage of water was another concern, and the same water had to be used for multiple purposes. All the time the heat was terrific. He noted that during September 1916, 32 Nursing Sisters left to form the staff of the 41st General Hospital, which was also with the Royal Serbian Army.

Arthur, himself was treated for malaria in October. He was recovered by Christmas 1916, which he described in some detail. Christmas Dinner consisted of turkey for the Officers and Nursing Sisters and pork for the Ordinary Ranks, who had been fattening two pigs for weeks. Musical entertainment was organised by the Serbs, whose band of the Timok Division stayed for the week. Football games between the two hospitals were organised, with separate competing teams of officers and men.

Scene after March 1917 bombing (Source: Français Opérateur K (code armée)., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

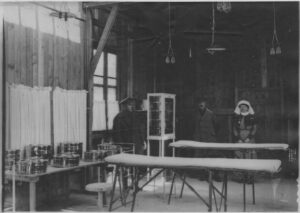

Arthur was on leave from 26 January to 18 March 1917. Upon his return he learnt that on 12 March Vertekop had been subjected to a heavy air raid, the dump at the railway station having been hit and exploded. Twenty bombs were dropped on the hospital. Marquees were wrecked, one bomb exploded in the X-ray tent and the sterilising room of the surgical theatre was wrecked. Sisters Dewar and Marshall (QAIMNS) and Ptes Cozens, Filkin, Sarfaty and Sowrey (RAMC) were all killed.

Wounded soldiers in 37th General Hospital, 1918 (Source: Français Opérateur K (code armée)., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Other issues he noted during the year included the awarding of Croix de Guerre medals to some Nursing Sisters, Officers and Orderlies of the 36th and 37th for their work during the March air raid. In June, Lieutenant Colonel N Tyacke took over command from Lieutenant Colonel Buist and that month a mountain convalescent camp was identified for the hospitals. There were two train accidents in September and October. Christmas was again celebrated by an ‘uproarious dinner, followed by foolish games!’

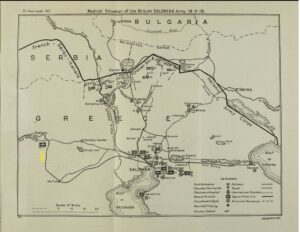

Medical Situation of the British Salonika Army 18.9.18 (Medical Services general history, Vol IV facing p.142)

There was heavy snow in February 1918, but that did not deter the entertainment schedule; Arthur recorded that two concert parties were held that month. Later diary entries were less about the hospitals and more about the military actions. The French had to round up disarmed Russians who had run amok in the area and preparations took place for the ‘great offensive’, as much artillery and heavy guns arrived.

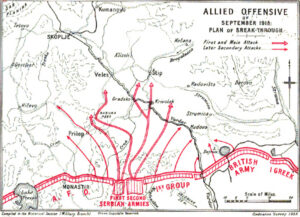

Allied Offensive of September 1918: Plan of Break-Through (Ordnance survey, 1935, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

He described some of the September military offensive. On 17 September 1918, the wounded received at the 37th hospital were mostly French and French Colonials, as the Serbs were sent to the 36th. ‘It was notable that during these first few days of the offensive, British casualties were roughly double those of the combined Serbian and French armies on the break-through sector. In a temperature of around 100 degrees in the shade, British troops, many of them rotten with malaria, were fighting uphill in gas masks, to meet healthy Bulgars waiting in their three lines of trenches with machine gun nests. Every valley was enfiladed, every spot where men could collect was registered by Bulgar artillery. Sept. 24th: Prilep has fallen; 20 locomotives have come into Serbian hands. All A.S.C. companies have moved up, also the Scottish Women’s Hospital from Dragomanci Valley’.

Staff at 37th General Hospital 1918 (Source: Français Opérateur K (code armée)., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

On 30 September 1918 he recorded: ‘Official news that Bulgaria had made unconditional surrender’. However, there was no immediate respite for the hospitals as during October there were many deaths from the Spanish ‘flu. He continued to record that ‘Turkey surrendered on 1 November’ (Mudros Armistice with Ottoman Empire on 30 October), ‘Austria followed suit on 4 November’ (Armistice of Villa Giusti with Austria-Hungary on 3 November) and ‘on 11 November, General Armistice at 11am; followed two days later by dinner and a concert at 37th to celebrate’.

Arthur concluded his diary with a description of his visit to the Devil’s Eye on Grand Couronne, perhaps the strongest natural fortress in Europe, and in a final summing up of the 37th General Hospital he wrote: ‘Our patients were mainly Serbs, though at the end we must have had some 20 nationalities, if not more. The Serbs are a handsome race, heroic fighters, and when wounded, stoical under pain. They had a great sense of humour. We had the greatest regard for these soldiers and no doubt, too, they had a high regard for the British’.

For his work in Salonika, Arthur was awarded the French Croix de Guerre (Supplement to The London Gazette, 21 July 1919, p.9220) and the Serbian Order of St Sava (Supplement to The London Gazette, 28 January 1918, p.1376).

After the war

Arthur was demobilised in March 1919 and returned to general practice in London. By 1923, his entry in the Medical Directory showed that he was then working with a new partner, Dr Hector Demetrius Apergis, but his address was still 55 Crouch Hall Road, Crouch End. Dr Apergis had also served as a Captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps during the war. Arthur remained in London until 1925, when he and his family moved to Godmanchester in Huntingdonshire. They lived in Fox House on Post Street in Godmanchester. He was in general practice there until 1946. In 1927 he was also appointed Honorary Medical Officer and Radiologist to Huntingdon County Hospital. He retained that post until 1951, when, aged 65 he retired from medical practice due to the National Health regulations at the time.

Dr Arthur Atkins Greenwood in 1961, The Mosquito, No. 137, March 1962 p. 14 (© Salonika Campaign Society)

That same year, together with his wife and daughter, he emigrated to Kenya, where he took charge of the X-ray department at the Nakuru War Memorial Hospital. The Nakuru War Memorial Hospital had been established shortly after the First World War to commemorate troops, both African and European, who had fought in the war. It had been officially opened by Dr Norman Jewell, another British doctor who had served as a Medical Officer in East Africa during the war.

Arthur finally retired in 1954 but remained in Kenya and died in Mombasa in 1978.

He had been a staunch member of the British Legion and the Salonika Reunion Association, and his contribution to the latter was that he played a key role in the establishment of the local branch for Huntingdon and District.

About the Researcher

Dr Arthur Greenwood’s story has been researched by Lyn Edmonds, who was the Project Lead for ‘Away from the Western Front’ and has remained interested in telling the stories of those who served in the less well-known campaigns of the First World War. Lyn has undertaken family history research for many years and has researched many of the soldiers’ stories on this website.

Lyn was formerly the Project Lead for the ‘Gallipoli Centenary Education Project’, which was also funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund during the centenary of the First World War.