Salonika

Away from the Western Front commissioned this film about the Salonika Campaign.

The film was written and narrated by Alan Wakefield, who also wrote the article below. A film transcription is made available courtesy of Sandham Memorial Chapel.

Salonika Campaign

The Salonika Campaign began on 5 October 1915 with the landing of the 10th (Irish) Division and French 156th Division at the port of Salonika in Greece. The rationale for sending troops to the Balkans was to deter Bulgaria from joining Germany and Austria-Hungary in an attack on Serbia. At the time, few Allied military and political leaders believed this would be a long-term commitment. However, lack of British and French military success on the Western Front and at Gallipoli, along with German victories against Russia, made Bulgaria believe victory for the Central Powers was a serious possibility and on 13 October 1915 she declared war on Serbia. Attempts by the Anglo-French force to support the Serbian army ended in failure and by 14 December the troops were back on Greek territory and retreating towards Salonika. By this date and despite British misgivings, Allied war leaders had decided to maintain their military commitment to the Balkans in the hope of bringing Romania into the war and ensuring the maintenance of Greek neutrality.

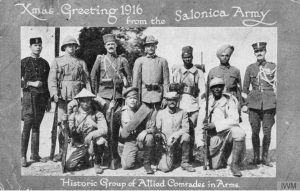

In terms of military forces engaged, the Salonika Campaign was perhaps the most diverse of the First World War, as shown in the Christmas card produced in 1916 (right). By 1917 the Allies fielded 600,000 men in six national contingents: British, French, Greek, Italian, Russian and Serbian. Within the British and French forces were also found units from India, French Indochina, North and West Africa. At peak strength the British Salonika Force (BSF) under Lieutenant General Sir George Milne numbered 228,355 officers and men. This included six infantry divisions divided evenly between XII and XVI Corps. In support, the British also employed volunteer units such as a Mule Corps and the Maltese Labour Corps. Australian, Canadian and New Zealand medical personnel were also part of the BSF, and the volunteer Scottish Women’s Hospital had units attached to the Serbian army. From January 1916 Allied forces were placed under the command of General Maurice Sarrail, reflecting the primacy of French forces in this theatre of war and greater French interests in the Balkans. Although appearing strong on paper, this Allied army lacked sufficient manpower, ammunition, equipment and supplies to fight a sustained campaign along a 250 mile front against an opposing force numbering almost 500,000 men. These troops comprised the Bulgarian army reinforced by varying numbers of Austro-Hungarian, German and Turkish units.

Allied offensives led by French and Serbian troops were launched during late 1916 and spring of 1917. As part of these operations the BSF fought the First Battle of Doiran (24 April – 9 May 1917) suffering 5,024 casualties. Failure by the Allies to break Bulgarian resistance resulted in stalemate along the Salonika Front. Soldiers on both sides faced each other for three years across challenging terrain, through extremes of climate in summer and winter. Accommodation for the front line soldier usually comprised little more than a bivouac tent or dugout. Much effort was expended on improving the local road network and in constructing light railways. Even so, many parts of the front could only be reached by pack mules. Disease, in particular malaria, proved endemic throughout the campaign. The BSF alone suffered 162,517 cases of malaria, the majority occurring in units serving with XVI Corps in the Struma Valley, at the time one of the worst malarial areas in Europe. Rates of infection were such a problem in the valley that both XVI Corps and their Bulgarian opponents withdrew to the hills during summer months.

A Bulgarian telephone station with trench periscope observing the Allies’ position at the Doiran front, March 1917 (Source: Wikipedia)

In 1918 a new Allied commander, General Louis Franchet d’Espèrey, planned an ambitious offensive. On 15 September, French and Serbian divisions attacked Bulgarian positions in mountains east of Monastir. Within three days these troops broke through the defences and continued to advance northward. In support of this operation the BSF again attacked the strong Bulgarian defences at Doiran on 18 September. Weakened by malaria, influenza and the withdrawal of units to the Western Front, the BSF was strengthened by the arrival of the Greek ‘Crete’ and ‘Serres’ Divisions. These formations played a lead role in two days of hard fighting at Doiran. Suffering 7,103 casualties, the British and Greek troops failed to dislodge the Bulgarians despite determined efforts and the capture of front line trenches. However, the attack achieved its main objective as not a single Bulgarian soldier left the Doiran sector to assist their comrades west of the River Vardar, against the continuing advance of French and Serbian forces. On 20 September, with their lines of communication threatened, the Bulgarian army was forced into retreat along the entire front. Pursued by Allied troops, and bombed in mountain passes by the Royal Air Force, the retreat became a rout. With foreign troops on Bulgarian soil, peace emissaries were sent to d’Esperey on 26 September. Three days later an armistice was signed, coming into effect on 30 September. After almost three years of stalemate the campaign ended in dramatic fashion in just sixteen days.

Text by Alan Wakefield, Head of First World War and Early 20th Century Conflict at the Imperial War Museum, courtesy of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.