Colonialism

A century ago the world was a very different place. It was dominated by a number of European empires, the largest being British, French, Ottoman, Russian and German. A major root cause of the First World War was imperialism: Britain had a well established world empire, as did France and other European countries like Portugal and Russia, and the Ottoman Empire was in decline but still controlled most of the Middle East. Germany was relatively new to the game and saw opportunities to expand beyond Europe. The various commitments to alliances which led to the actual outbreak of war in 1914 were the enactment of these geo-political forces. The assassination in Sarajevo was the spark which ignited the competition for global influence and control. As it turned out, however, the war started a process which would lead ultimately to the end of these global empires.

How were colonial troops mobilised?

Once the war started, the various empires turned to their colonies for support. Britain asked its dominions (self-governing countries within the empire: Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland and Canada) to send troops and supplies, and all of them did. Britain’s colonies (i.e. countries directly ruled by Britain, including India, parts of Africa and the West Indies) were also encouraged to support the ‘Mother Country’. From the outset, the British colonies and dominions were fiercely patriotic and regarded themselves as ‘British’: all were volunteers (although it has to be said that ‘recruitment’ in India and Africa in the later stages of the war was often more like coercion), and conscription was only introduced in Canada and New Zealand.

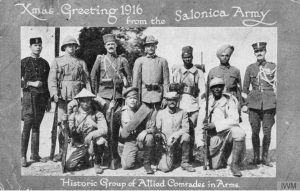

Meanwhile France called on its colonies in North and West Africa, Madagascar and Indo-China, but used conscription to recruit the armies, which would later lead to an anti-imperial backlash after the war. Germany raised troops in its colonies in West, South West and East Africa, to defend these when British colonial troops invaded at the start of the war. The Ottoman Empire was older and more homogeneous than the European empires; like the European armies, the officer positions were mostly held by the ruling class (i.e. Turks), with Arabs and Kurds making up most of the other ranks. The Ottoman Empire was able to mobilise its troops using long-standing systems of hierarchical control based on the Anatolian centre of power, especially Istanbul where the military elite were trained.

What did colonial troops do during the war?

The only non-white colonial troops used by Britain for combat on the Western Front were four Indian Army divisions, and two of these were redirected to Mesopotamia after a year. The vast majority of British colonial troops were used in campaigns away from the Western Front, because it was felt that they were better suited to fighting in hot climates. The Indian Army provided most of the manpower in the Middle East, and black soldiers from the Caribbean, West Africa and East Africa were drawn into various conflicts in Africa.

As a long-established British-led army, which included several British regiments, the Indian Army was given combat roles in all theatres. However, racial attitudes at the time meant that, in general, white Europeans felt that it was unacceptable for black colonials to fight against their colonial masters. This was partly due to a fear that they might get a taste for insurrection, which could lead to armed uprisings and calls for independence in the colonies. Dominion troops were treated as equal and allowed a full role in the war but many black colonial troops were excluded from front line combat and given support roles such as building railways and delivering ammunition. There were exceptions: in Palestine the British West Indies Regiment were sent into combat (significantly, by a New Zealand general) – see more on our West Indies page. Some colonial volunteers were confined to ‘Labour Corps’, never rising above the role of servant to European troops. These included Egyptian, Maltese, African and Chinese corps.

Unlike the British, the French were willing to use their West and North African troops on the Western Front, fighting the Germans. This was partly due to the fact that they had lost so many men of their own on the Western Front that there was little alternative. After the war they even used their black West African soldiers to garrison the Rhineland – an insulting and provocative act in view of German attitudes to race at the time. Again, the fact was that they had very few native Frenchmen to spare.

German colonial troops in Africa were formed into forces in the same way as British troops – native soldiers and carriers under the command of white European officers. However black German colonial troops were never used on the Western Front, against other Europeans.

In the theatres away from the Western Front, therefore, the pattern was for armies consisting of colonial men under the command of white officers, pitted against similar forces. In East Africa, for example, by the end of the war the campaign was being fought between regular British African troops (the King’s African Rifles) under the command of white British and South African officers, supported by locally-raised carriers, against the German African askaris, under the command of white German officers, again supported by locally-raised native carriers.

What was the effect of the war on the colonies?

With huge numbers of young, fit men taken away from what were mainly agricultural societies, and harvests routinely requisitioned to feed the armies, there was an immediate impact on the colonial economies. In some cases, this had disastrous effects: when famine struck in German East Africa in 1917 the country did not have the manpower or food reserves to respond, and 300,000 civilians died. Although not a colony, Persia (Iran today) suffered a similar fate, as British forces occupying the country requisitioned food for their huge army in Mesopotamia, leading to a famine in which perhaps a million people died. See our Persian pages for more information.

There were further ill effects when the troops returned after the war. Over the previous four years, economies had shrunk and jobs were not necessarily available for the ‘returning heroes’. In Jamaica, for instance, British West Indies Regiment (BWIR) volunteers found that not only were their former jobs no longer available, but they were seen as a potential source of unrest and many were sent to Cuba to work there in the sugar cane fields. This added to the sense of injustice felt by BWIR soldiers after their grievances about poor treatment while still enlisted, which led to the mutiny in Taranto in December 1918.

The British and Germans might have been justified in their fear that allowing black colonial troops to fight alongside white soldiers, and against other white European soldiers, was ill-conceived. It led to feelings of comradeship, and also increased their sense of power, as explained by Indian historian Vedica Kant.

Some colonial soldiers did not return until long after the armistice. The victors found that they now had vast new swathes of land to control: in the Middle East, after the break-up of the Ottoman Empire, Britain used Indian sepoys who had served there to provide the occupation force. The story of Sepoy Mohamed Ali illustrates this – he stayed in Iraq until 1928 and married a Christian woman from Mosul. After 14 years abroad, his links with his homeland had been all but severed.

Was the First World War the end of imperialism?

The war led directly to the collapse of the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, German and Russian empires – the first three because they were on the losing side and the last as a result of the Russian Revolution of 1917. However for Britain and France the victory led to major expansion of their empires, as they stepped in to control German colonies in Africa and Ottoman territories in the Middle East. Indeed imperial expansion was to some extent a British strategy during the FWW, especially in the Middle East, control of which was linked to its need for oil and to the protection of its routes to India. Nevertheless in the immediate aftermath of the war Britain faced calls for independence from Ireland and political unrest in Egypt, India and the Caribbean. The image of Britain as a benevolent imperial ruler was seriously tarnished by the way it had to resort to the use of force to control these post-war uprisings, especially in India with the brutal massacre of non-violent protesters in Amritsar.

The French Empire was hit by armed uprisings in Morocco, Indo-China and its African colonies. The fact that France had conscripted its colonial troops was partly to blame for this: it implied that the men were citizens, with a duty to their government, leading to a demand for rights. Italy tried unsuccessfully to retain control of its colonies in North Africa, while Portugal faced uprisings in Angola and Mozambique.

Possibly more significant were domestic attitudes to imperialism: with the introduction of socialism and the widening of the vote, it was far less attractive on moral grounds. A further anti-imperialist influence came from Russia and America. The Russian revolution had ended the Tsarist Empire, and the Bolsheviks wanted a new internationalism based on socialist principles. President Woodrow Wilson was firmly against imperialism and attempted to limit British and French imperial ambitions through the establishment of the League of Nations. Britain and France paid lip service to this but their imperial policies did not change substantially after 1919. Instead they worked within a system of mandates.

How were mandates used to manage former colonies?

Britain and France divided up the German and Ottoman Empires but resisted pressure from the League of Nations to allow the former colonies to rule themselves. Instead they used the system of mandates, theoretically ruling the new states on behalf of the League. In some cases (e.g. in the Middle East) these mandates were presented to local populations as ‘interim governments’, offering advice while representative national administrations were established. In others (e.g. in Africa) they were little more than a change of colonial ruler, with minimal representation. A third type of mandate awarded control of a colony to a third party: this was the case in South West Africa (Namibia today) which was ‘given’ to South Africa and German New Guinea (Papua New Guinea) to Australia. The mandates were overseen by a Commission at the League and although the system did little to change colonial-style rule, it did at least offer an international forum where people could complain about abuses in their countries. Through the League of Nations the principle of international accountability was established, altogether different from traditional 19th century imperialism.

Conclusion

The First World War led to the end of four empires, but the victorious empires profited from this, adding to their territories and creating even larger empires. However even in these larger post-war empires the seeds of de-colonisation had been sown, which would mean that they would be unable to survive a second world war. Between the wars there were growing nationalist movements in countries formerly under colonial rule. When the colonies were called upon for a second time, the earlier argument that they were supporting the ‘Mother Country’ was harder to justify. The remaining great 19th century European empires would collapse after 1945.