‘Manchester Column’

A series of incidents took place throughout the summer of the 1920 revolt in Iraq and increasing civil disobedience took hold. In one particular incident, the railway at Al Kifl, south of Baghdad, was attacked and the local Political Officer requested assistance from the British army garrison at Hillah to restore order. On 23 July a military force was sent south to assist.

This British-Indian force, now known as the ‘Manchester Column’, included:

35th Scinde Horse (2 squadrons)

39th Battery Royal Field Artillery (2 sections)

2nd Battalion Manchester Regiment (3 companies)

1/32nd Sikh Pioneers (1 company)

24th Combined Field Ambulance (1 section)

In addition, a transport train brought the total strength to around a thousand.

The column commander was Brevet-Lieutenant Colonel R.N. Hardcastle DSO. Before leaving Hillah, Lieutenant Colonel Hardcastle had been under the impression that he was the advance guard of a larger force that would follow his column, and his orders were, ‘If opposed by large hostile forces, you will avoid becoming so involved as to necessitate reinforcements and should occasion arise you will fall back on the position you now occupy’. However, he was unaware that there was no larger force, and his column was alone in an increasingly hostile area.

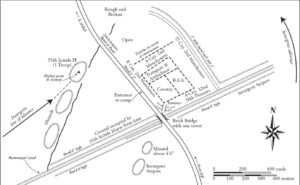

By 24 July, the column reached the Rustumiya Canal at about 12:35 hours. The Manchester Regiment soldiers were so exhausted by the extreme heat that the Medical Officer recommended a 24-hour rest period and camp was struck. At 17:45 a force of some 3000 insurgents approached the camp. The insurgents advanced at some points to within 150 yards from the camp and fire was exchanged. Real concerns that the column would be surrounded if it remained in place were raised, and the decision to withdraw was made. One company of the Manchesters acted as advanced guard whilst the other two companies marched on the flanks. The transport train followed the first company, followed by the guns escorted by the Sikh Pioneers; the two squadrons of Scinde Horse acted as rearguard. The column headed back towards Hillah after 20:00, as per orders not to engage.

It was not long before chaos ensued, as the horses in the retreating column in part panicked and the men became disoriented in the dark. A summary is encapsulated by this account of a Victoria Cross award to Captain George Stuart Henderson DSO, MC & Bar, 2nd Battalion Manchester Regiment. The citation for his posthumously awarded VC states:

‘Shortly after the company under his command was ordered to retire near Hillah, Mesopotamia, a large party of Arabs opened fire from the flanks causing the company to split up and waver. He at once led a charge which drove the enemy off. He led two further bayonet charges, during the second of which he fell wounded but struggled on until he was wounded again’.

‘I’m done now. Don’t let them beat you!’ he said to an NCO’.

‘He died fighting’.

Order was eventually restored. The Commander-in-Chief later wrote:

‘The officers of the 39th Battery and those of the cavalry behaved like heroes and it is thanks to their fine example and the discipline of those under their command that a complete disaster was averted’.

However, some of the Manchester Regiment and other parts of the column, having become lost in the dark, fell into the hands of the Arabs. Some were killed immediately whilst others were taken prisoner.

During the night Company Sergeant Major (CSM) Charles Mutters of D Company reportedly gathered a group of 79 soldiers around him, including Company Quartermaster Sergeant (CQMS) Edward Harvey and as they were not able to get back to Hillah they had to surrender at dawn. The prisoners were initially held by tribal leaders, led to Al-Kifl on foot and then moved to Abu Sakhair and finally to Khan al- Shilan, probably arriving there on 28 July, where they remained for three months.

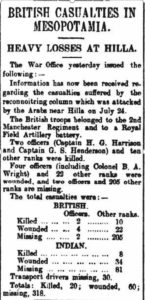

Most of the British casualties in this incident were from the Manchester Regiment. There were conflicting reports of the numbers, but it is thought that 20 were killed, 60 wounded and 318 missing presumed captured or dead. Of the 318 missing, 160 were released at various times by their captors. It was estimated that 100 prisoners from the Manchester Regiment were tortured and executed by their captors.

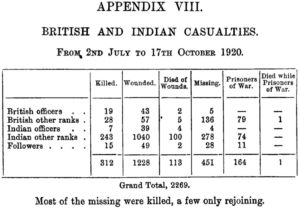

Insurrection in Mesopotamia 1920, Appendix VIII, by Lt. General Sir J Aylmer Haldane (W. Blackwood and Sons, 1922)

Insurrection in Mesopotamia 1920, Appendix VIII, by Lt. General Sir J Aylmer Haldane (W. Blackwood and Sons, 1922) – but it should be noted that it covers all casualties from 2 July 1920 to 17 October 1920.

After a few months, the rebels in Mesopotamia began to run low on supplies and funding and could not support the revolt for much longer, and the British forces had become more effective. The British Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, authorised reinforcements that included two squadrons of the Royal Air Force. The use of aircraft shifted the advantage to the British and played a huge role in ending the revolt. The revolt ended in October 1920, when the rebels surrendered Najaf and Karbala to the British authorities.

The prisoners in Khan al-Shilan were released on the 19 October 1920.

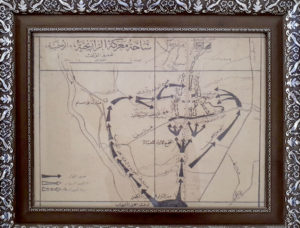

In Iraq the fighting against the ‘Manchester Column’ was named the Battle of Alrarinjiya (or al-Rarinjiya) and was depicted in this map which shows the opposing forces and the retreat. This is a framed copy, which is on the wall of the museum. It is entitled, ‘Official field of the al-Rarinjiya Battle’ and the arrows in the key are as follows:

black arrows are the Iraqis, labelled ‘the Revolutionary Army’

white arrows are the British, and

dotted white arrows represent the British retreat