East Africa

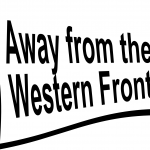

Belgian troops and native Congolese porters crossing into East Africa, 1918. (Source: Wikipedia)

The campaign in East Africa was a showdown between the British, Belgian and Portuguese Empires on the one side and German Empire on the other. Mainly taking place in German East Africa (modern-day Tanzania), most of the fighting was between black African troops raised in the colonies, led by European officers. The fighting took place over a massive area three times the size of the German Reich. It was long-drawn-out and extremely costly both in terms of loss of life and use of resources. The death toll was estimated to be 105,000, similar to the number killed in the Battle of the Somme (July – November 1916). However, what made it different from the Western Front was that the majority of the deaths were due to disease, and most of the dead were local people.

Why did the First World War come to East Africa?

The East African campaign in many ways happened by default, although it is regarded by some as the final stage in the ‘scramble for Africa’. In less than thirty years nearly all of Africa had been colonised by European nations.

At the start of the war German colonies were surrounded by colonies controlled by Entente allies. Germany had grand plans for a huge African Empire (‘Mittelafrika’) if it defeated the Allies, as did Britain, running the length of Africa epitomised in the Cape Town to Cairo Railway line.

Far from being an irrelevant sideshow, the East African campaign was for Europe an opportunity to realise imperial ambitions.

As the military historian Harry Johnston put it, ‘the Great War was more occasioned by conflicting colonial ambitions in Africa than by German and Austrian schemes in the Balkans and Asia Minor’. For the local populations, settler and indigenous, it was another of a string of wars, disrupting the status quo and the challenge of taming the land for mass cultivation along European lines.

What happened?

At first – as in Europe – the colonists living in East Africa believed that ‘it would be all over by Christmas’, especially as the armies facing each other were tiny – 2400 in the King’s African Rifles in British East Africa and Uganda, and 2700 Schutztruppe in German East Africa. Both forces consisted of black and Arab rank and file. In August 1914, the German occupied the area of Taveta in today’s Kenya and disrupted rail supplies. In November 1914, the British felt in a position to send two Indian Expeditionary Forces to East Africa, one to defend British East Africa (Kenya) and the other to invade German East Africa at Tanga. At this stage, occupation of the German colony would ensure the safety of the Indian Ocean sea lanes for Britain. It was only after 1916, that the desire turned to imperial ambitions.

Lack of co-ordination (eight government departments), inaccurate intelligence, an underestimation of the enemy’s ability and mismanagement resulted in the 8000-strong invasion force being beaten back by just 1,000 German askaris (locally recruited soldiers). When the British troops sailed off they left behind modern rifles, 16 machine guns and 600,000 rounds of ammunition, which would be used against them in the months ahead.

The War Office, which had assumed control of operations in the theatre refused to sanction action unless there was a guarantee of success. The British were forced onto the defensive in the north. In the east of the German colony, the Belgians and British were working together to obtain control of Lake Tanganyika which they did when the two British gunboats Mimi and Toutou captured the German Kingani and sank the Herman von Wissmann. In the south, the local forces in the Rhodesias and Nyasaland held their own until Edward Northey was appointed commander of the Northern Rhodesia – Nyasaland Field Force and started pushing north into German territory at the same time that the campaign on the British-German East Africa border was relaunched with the arrival of the South African forces in February 1916.

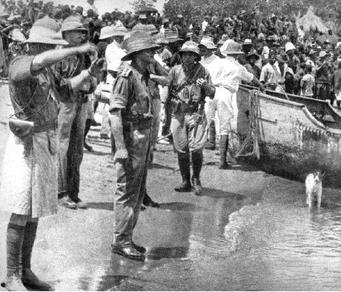

Von Lettow-Vorbeck’s surrender, 25th November 1918. The picture is revealing: by then, both forces were made up almost entirely of black native troops. The Germans were using pre-industrial transport while the British had been able to bring in some motorised transport. It is also one of the few images from the time by a black African artist. (Source: Wikipedia)

The year 1916 saw an increase in action as the British and Belgian forces forced the Germans into the south-west of the German colony. Portugal officially entered the war in March 1916, having been neutral until then. From late 1916 the war became more mobile with the Allied British, Belgian and Portuguese forces trying to bring the Germans to fight.

In 1917, the Germans moved into Portuguese East Africa before finally returning to German East Africa and then moving into Northern Rhodesia where on 13 November 1918 they were notified of the armistice in Europe. The Germans surrendered in Abercorn (Mbala) on 25 November 1918 and on 19 February 1919 left East Africa to return to Germany.

Did you know?

- The Battle of Tanga has been called the ‘Battle of the Bees’ because there were numerous bees’ nests in the trees on the battlefield. When the shooting started they swarmed out and stung the soldiers, forcing them back. When combined with fire from the German machine guns, this turned the tide of the battle. In fact the Germans suffered as much as the British from bee stings. Other battles of the bees took place elsewhere in East Africa where hives were prevalent.

- This was a very multi-national campaign. Only two British regiments were involved. The 2nd Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment arrived with the Indian Army invasion force at Tanga and after this stayed on the border between British and German East Africa. The 25th Royal Fusiliers (Legion of Frontiersmen) was raised for service in East Africa in early 1915. It served throughout the war. In addition, white contingents were supplied by Rhodesia in 1914 and 1915, the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment, Nyasaland and South Africa including the South African Expeditionary Force which arrived in February 1916. In December 1916 the majority of the white troops were withdrawn to South Africa to recuperate; those fit enough returning to service in East Africa, Mesopotamia or Europe. Most of the Indians returned to India (i.e. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) whilst some stayed for the duration. From mid-1916, the composition of the British forces changed with the arrival of the Nigerian and Gold Coast (Ghana) contingents and the expansion of the King’s African Rifles from 3 battalions to over 20. The main fighting force now consisted of mainly black African men. In total, it is estimated that 177 micro-nations (tribal groups of all ethnicities) participated in the East Africa campaign.

- The German cruiser SMS Königsberg was guarding the colony when war began, but it badly needed an overhaul. The crew camouflaged the ship and hid it in the mangrove swamps of the Rufiji River Delta in October 1914. The cruiser was eventually traced and put out of action in September 1915. The 10 guns of the Königsberg and the 6 from the British cruiser Pegasus, sunk by the Königsberg in Zanzibar harbour, were converted for land use.

- The search for the Königsberg saw the first use of planes in East Africa. In addition to the hydroplanes used to find the Königsberg and to spot for the monitors (shallow draught gunboats) attacking the ship, two British planes were used by the Belgians to push the Germans out of Kigoma. In 1915, the Royal Naval Air Service introduced aircraft near Taveta which was eventually replaced by the 26th Air Squadron consisting of mainly South African pilots. The 8th Air Squadron was based at Zanzibar. The Germans had one plane which was crashed early in the war.

-

In November 1917, the Germans tried to overcome the immensely long supply chain for their troops by sending a Zeppelin from Europe (Bulgaria) to Africa. The huge airship (L59) was given a one-way mission. Its canvas envelope was to be used for tents, its metal framework for telegraph masts and stretchers and its leather walkways for boots. It also carried 15 tons of supplies – machine guns, ammunition, food, quinine and other medical essentials. The L59 got as far as Khartoum, when it received a message that the German force had moved into the mountains and the airship was likely to fall into British hands, so they turned back. At 95 hours non-stop flying, the journey still holds the record for the longest-ever military flight. The Germans succeeded in getting two ships to break the blockade to East Africa, one of which, the Kronberg was crewed by Danes from Schleswig-Holstein, then controlled by Germany.

-

Lake Tanganyika formed the border between German East Africa and the Belgian Congo, and the German navy controlled the lake with a few small gunboats until December 1915. To win naval control of the lake, allowing Belgian troops to attack from the west, the only way was to carry boats overland. Under the command of the very eccentric Captain Geoffrey Spicer-Simpson, two fast motor launches named HMS Mimi and HMS Toutou were shipped out from Britain and transported overland by train from South Africa to Katanga in the Belgian Congo, including an extraordinary trek which included 146 miles through mountains, using two steam tractors, teams of oxen and hundreds of African porters. 150 bridges had to be built along the way. Eventually, the two boats arrived at Albertville (Lukuga) mid-way up Lake Tanganyika and captured the German gunboat Kingani, which Spicer-Simpson renamed as HMS Fifi, before gaining control of the whole lake.

Was the campaign different from others?

It was very different from all the other campaigns of the First World War. Besides covering such a large area, it was a very mobile campaign, with immense logistical challenges and an extremely hostile natural setting. The British could use their naval supremacy to supply their forces and those of their allies, which was not the case for the German army. With depleting forces, the Germans, under the determined leadership of Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, were able to hold on to the end of the war, helped by weak Portuguese resistance which allowed him to resupply at a crucial time. In the few battle encounters such as at Mahiwa, both sides lost significant numbers of their fighting force. Although Lettow-Vorbeck did not succeed in attracting large numbers of fighting men from the Western Front (most of those who fought in Africa would not have fought in Europe) he did succeed in keeping ships occupied and holding the attention of the European war leaders.

A very hostile environment

The East African theatre of war was extremely challenging and the environment was regarded by all as the biggest enemy. Some men wrote home that they would rather be on the Western Front where they could be shot by a sniper than have to deal with wild animals, the weather, jigger fleas and ambushes in grass six foot high. The landscape was undeveloped, with few roads or railways, so the use of wheeled transport was almost impossible and animals such as oxen and mules soon died in the tropical conditions. This meant that all armies relied on huge numbers of porters, initially volunteers but later conscripted. Porters and labour were raised locally, and also came from Sierra Leone, the Seychelles, China and Southern Africa.

Long lines of communication

The distances were immense. Supplies were sent from India and Durban, the latter travelling 1,500 miles to the railhead, then transferring to carriers for the additional 450 miles through the bush to the front. To carry just one ton of supplies took 16,500 carriers, and one ton of food was enough to feed the soldiers for one day. In fact, only 2,500 carriers were needed to carry the food for the soldiers; the additional 14,000 carriers had to carry the food for the other carriers! During the campaign, it is estimated that 1 million carriers were recruited, of which, it is believed, a staggering 95,000 died, almost entirely due to poor rations, sanitation and medical care. The medical failings were so concerning – 75% of the armed forces were lost to malaria, dysentery, blackwater fever and malnutrition – that the War Office ordered an inquiry – the Pike Report – which is the focus of our Health – The Hidden Enemy project.

How did the war affect East Africa?

The impact of the war on the people of East Africa was dire. Many families were affected, either because of involvement in the Carrier Corps or armed forces, or because crops were requisitioned, leading to starvation and poverty; a situation exacerbated by flooding and drought. When famine struck in East Africa in 1917 the civilian population did not have the manpower or food stores to respond; 300,000 civilians died in German East Africa alone. To cap it all, the Spanish Flu epidemic came in 1918, just as the war was ending. In British East Africa alone, 160,000 died – 10% of the population. Ironically, the epidemic would have been much less serious before the war, when African communities were much more isolated from each other; due to the new lines of communication crossing the region, the virus was able to move at devastating speed.

Germany lost the war, and its dreams of an African empire disappeared at the same time, but that was not the end of colonialism in Africa. Britain, France, Belgium and South Africa took over the German colonies. German East Africa became Tanganyika under the British and Rwanda and Burundi under the Belgians. The First World War was instrumental in creating the leaders who led their countries to independence forty years later.

Further reading

Further detail on the military and social aspects of the East African Campaign can be found in Paice, E., Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa (W&N, 2008), which has been the main source for this summary.

Fecitt, H. Harry’s Africa. The soldier’s burden, n.d. [Accessed 24 November 2021]. Available from: http://www.kaiserscross.com/188001/home.html

The Heroes of the East African Campaign of WW1. Guerrillas of Tsavo, 2020 [Accessed 24 November 2021]. Available from: https://www.heroes.guerrillasoftsavo.com/

Samson A., Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign 1914-1918: The Union comes of Age (IB Tauris, 2005)

Jewell, Dr N. P., On Call in Africa, in War and Peace 1910-1932, (Gillyflower Publishing, 2016) This book contains the story and eye-witness account of events based on the personal diary, memoirs and extensive photography of Dr Norman Parsons Jewell who served as a Medical Officer throughout the First World War in East Africa.

Moyd, Michelle R., Violent Intermediaries: African Soldiers, Conquest, and Everyday Colonialism in German East Africa (New African Histories) (Ohio University Press, 2014) This book sheds light on the German Askari.

The story of Africa’s involvement in the First World War still needs to be published; the main accounts being Eurocentric in approach.

Text by Dr Anne Samson, Great War in Africa Association.